My 10-year-old tells me he likes attending Friday night services at our synagogue because of the cookies served afterward.

My 10-year-old tells me he likes attending Friday night services at our synagogue because of the cookies served afterward.

Despite his eating more than the two or three treats we’ve agree on beforehand, I’m glad he’s also digesting important lessons about community values by being there.

A few weeks ago after eating his fill of sweets, he went up to our rabbi to ask a question about the sermon.

Rabbi Greene had described a peculiar tradition from ancient days about what the elders in a community did following a murder. They went to the crime scene and announced their innocence over the deceased victim.

It’s not that anyone had accused the community leaders, but by stating out loud that they weren’t at fault for the horrendous act, they were also proclaiming their broader responsibility for it.

Rabbi Greene explained how leaders and members of a community are responsible for one another.

If a man is killed, what was going on in his larger environment leading up to the incident? If a child goes hungry, how did the community allow for a situation in which that could happen?

I wondered, what are the boundaries of our personal responsibility for a civic atmosphere where hunger, hatred — or worse — remains?

Eli had a similar question for our rabbi. He asked, “What if that guy over there,” he pointed to a group of kibitzing worshipers, “left here and robbed someone? Is that really my fault?”

“I wouldn’t say it’s your fault,” replied our rabbi. But it’s the grownups around you who need to make sure no one goes hungry, that everyone’s needs are met, and ask what we can do to take care of our community, he explained.

I’m paraphrasing what I heard the rabbi say, but I take the message about our personal responsibility for creating the world around us to heart.

I want the leaders in my city to do the same.

A couple weeks ago in my small town, a swastika was scratched onto the door of a Jewish couple’s apartment – twice.

It left me pondering the society I live in, the one we all have a hand in creating, a society in which bold expressions of hatred exist. In Colorado, acts of anti-Semitism have more than doubled in the past year.

If my response is to just shake my head and post my outrage on Facebook, I’m not really owning it. I need to ask: “How have I participated in a social climate where anti-Semitic vandalism occurs? What more can I do?”

Imagine community leaders going to the scene of the crime and announcing, “Not it. It wasn’t me,” as in the Bible story my son and I had been mulling over.

Sounds foolish, doesn’t it?

Denying a crime in that manner could be interpreted as saying, “it’s not my fault and therefore not my problem.”

But folks’ more typical reaction of expressing outrage over an incident and then moving on with their busy lives is not much better.

What if instead of just pronouncing, “No, we will not tolerate hate and acts of violence against one another,” we added, “I take responsibility for someone targeting a Jewish family in my town”? “Let me examine how I am complicit.”

What if we challenge ourselves by asking, “What could I have done to build a more inclusive, compassionate and just society? How can I be proactive in that regard from now on?”

I think these are questions we all can ask. If we want to learn from the past and have a better tomorrow, I believe we must.

Consider the two city-promoted opportunities for citizens of Lafayette, Colo., where I live, to meet potential city council candidates. The first event was set for the eve of Rosh Hashanah, one of the most significant times of the year for Jews – a day where Jewish people avoid engaging in work and social activities. The second candidate forum is scheduled for Simchat Torah, another one of the Jewish high holy days.

Setting the events on those holidays is like setting an election event on Christmas Eve. It wouldn’t happen in America.

Sure, Jews can catch the candidates’ forum on video feed after the fact, (if technology complies) but scheduling opportunities for citizens to meet their potential representatives and ask questions in person on days when Jews are inherently excluded leaves a perception that not all are welcome. It comes across as alienating and dismissive of an entire minority population. It maintains a group of people as the Other and inadvertently leaves people susceptible to being overlooked and ostracized further — and perhaps ultimately mistrusted, hated and condemned.

People in Lafayette like to say we are building an inclusive community. I believe this means that in addition to what we say, our city and fellow citizens must continually examine our actions (including those we fail to do) and recognize that perception is reality.

The Anti-Defamation League’s A World Of Difference program that teaches communities how to recognize and confront bias states that “attitudes and beliefs affect actions, and that each of us can have an impact on others, and ultimately, on the world in which we live.”

The Anti-Defamation League’s A World Of Difference program that teaches communities how to recognize and confront bias states that “attitudes and beliefs affect actions, and that each of us can have an impact on others, and ultimately, on the world in which we live.”

So it isn’t enough to claim we’re inclusive of all religions, colors, genders, backgrounds and abilities. We have to scrutinize where we inadvertently exclude, where we fail to bridge differences, and seek opportunities for actively including others and for social connection.

We need to take responsibility for our role in manifesting the community around us.

The city of Lafayette’s public information officer did just that. She apologized for forgetting to consult the calendar the ADL sends to local governments that lists religious holidays to consider when planning community gatherings.*

A few days after I told her that the candidate forums were set for Jewish holidays, she changed one of the dates. Instead of September 20, 2017, as originally planned, the first forum took place September 25.

A few days after I told her that the candidate forums were set for Jewish holidays, she changed one of the dates. Instead of September 20, 2017, as originally planned, the first forum took place September 25.

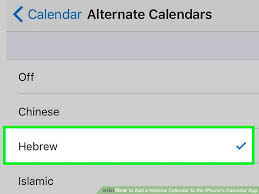

I applaud the communications director’s ownership of the problem and steps to fix it because it makes a positive impression and supports Lafayette’s inclusive ideals. That makes our community more resilient. I bet city staff will remember to check alternate calendars in the future on behalf of all citizens.**

Certainly a scheduling mishap should not be conflated with carving a symbol associated with Nazis and the murder of millions on a neighbor’s home, but perhaps awareness of others’ holidays and working to include all kinds of people in one’s planning fosters an atmosphere where bigoted thinking and acts are prevented.

If we take collective responsibility for both incidents and choose to seek ways to do better, perhaps we can influence positive perceptions and change our climate for the better, too.

* Event planners need to consider that Baha’i, Jewish and Islamic holidays begin at sundown the previous day and end at sundown on the calendar date listed for most calendars.

** Earlier this week, on September 26, 2017 , Lafayette’s Human Rights Commission decided to act on ensuring city staff check for religious holidays and other potential conflicts prior to scheduling events.

Big my boys ended up missing things this past weekend due to Yom Kippur. For S, he missed a Boy Scout camping trip that he really wanted to attend. And for Z, he missed his Cub Scout kickoff meeting for the year. Made me sad that those events were scheduled for this weekend.

I get it. I’m sad too. This has gone on our entire lives. Share the ADL calendar with the organizations. Explain why it’s discrimination or at least alienating and excludes.